Every year we do a story about timing belts, how they work, why they are necessary, and how to keep your engine together before it self-destructs when the belt breaks.

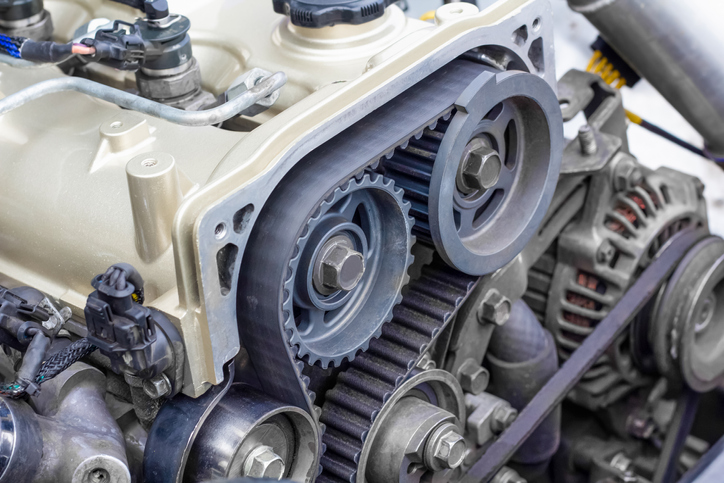

The timing belt is the belt that you never get to see. That’s because it is usually behind the motor mount and the serpentine belts, the alternator and power steering pump, and of course under the timing covers, which are there to protect it from road debris and other maladies. As the name implies, its function is to time the top of the engine (which includes but is not restricted to) the valve train and camshafts, to the bottom of the engine which is the crankshaft. As the newer vehicles have become more sophisticated and efficient, many of the tolerances and clearances have been made even tighter.

Multiple camshafts have become the norm, not the exception, so these “timing” specifications have become even more important. Imagine as many as four valves opening and closing in sequence to a piston going up and down while hitting speeds of close to 2500 RPMs. Now imagine those valves timing with each other so that the intake valve can open and close together so as to allow the fuel to enter the combustion chamber and then seal itself off so that combustion can occur and the exhaust valves to open to allow the expended fuel to be expelled into the exhaust system and then closed in time to allow the fresh fuel charge to be sucked back in. This is the combustion cycle. In the industry this is referred to as suck, push, blow and fart. Crude but descriptive.

Multiple camshafts have become the norm, not the exception, so these “timing” specifications have become even more important. Imagine as many as four valves opening and closing in sequence to a piston going up and down while hitting speeds of close to 2500 RPMs. Now imagine those valves timing with each other so that the intake valve can open and close together so as to allow the fuel to enter the combustion chamber and then seal itself off so that combustion can occur and the exhaust valves to open to allow the expended fuel to be expelled into the exhaust system and then closed in time to allow the fresh fuel charge to be sucked back in. This is the combustion cycle. In the industry this is referred to as suck, push, blow and fart. Crude but descriptive.

Years ago this was all done with a chain, which had a pretty long service life so long as the lubrication system of the vehicle was well maintained. Chains were eventually taken out of the vehicles for a variety of reasons, most notable being cost, noise, and weight. They are however starting to make a comeback in newer vehicles especially those vehicles with multiple cams and variable valve timing, but that is for another article.

So how does this giant rubber band play into today’s engines and what safeguards are there to protect them from breaking and making the engine self-destruct? First, the advancements in the rubber compounds help keep the belt from deteriorating from not only use but from heat. The second advancement was in the new design incorporated in the cog, the part of the belt that is actually driven from the crankshaft and then drives the cams. To design a piece of rubber that is flexible enough to maneuver tight turns around a pulley and resilient enough to stand up to the torqued applied by the driving pulley (the crankshaft). Then, to be able to drive at least one but usually, two camshafts is a tribute to technology.

First, timing belts hate oil. So if you see any oil leaks developing around the valve covers and by the crankshaft, chances are that this oil residue is going to end up on your belt thus shortening its life. These leaks should be repaired as soon as possible.

First, timing belts hate oil. So if you see any oil leaks developing around the valve covers and by the crankshaft, chances are that this oil residue is going to end up on your belt thus shortening its life. These leaks should be repaired as soon as possible.

Belts also hate coolant which is in itself a petroleum product. As most timing belts also drive the vehicle’s water pump repairing a water pump leak from the pump requires removing the belt anyway, but coolant leaks from the intake manifold or bypass hoses can also infiltrate the timing case and still contaminate the belt. Finally, a positive lubrication policy is imperative. This is just a fancy way of saying keep your oil changes current and timely with the proper grade of oil and quality filters reduce friction and relieve stress on all moving parts. That in itself is just good old-fashioned common sense.